The Big Picture - Hold Ratings Mean Avoiding a Buy Rather Than Being Neutral

By: Joseph Kalish

Stock analyst ratings, including buy, hold, and sell, influence investment decisions significantly. However, a nuanced examination of these three ratings, coupled with data from the AnaChart database and insights from academia, reveals an often overlooked trend: the overuse of the hold rating as a measure for when analysts wish to disassociate themselves from specific stocks.

AnaChart has the largest database of stock price targets available to the public; moreover, it has one of the most premium datasets for stock ratings, which is about 750,000 ratings after removing duplicates (a rating that is reported by more than one large media outlet on the same day) and corrupt ratings (human error). To simplify the research gathered, we have combined various synonyms of the same ratings into three categories: buy, hold, and sell.

References

Analysts issue hold ratings far more frequently than they issue sell ratings. Based on the AnaChart database, the total instances of maintaining a hold rating (hold-to-hold) stands at 188,329, vastly outnumbering recommendations to stay with a sell rating (sell-to-sell), amounting to just 28,490. On top of that, when analysts decide to downgrade a stock, they often switch to a hold rating rather than a sell, as evidenced by the 63,060 buy-to-hold changes, contrasted with the mere 2,587 buy-to-sell changes.

One study by Brad Barber, professor emeritus of finance at the UC Davis Graduate School of Management, and a 2005 Wall Street Journal article, highlight the scarcity of sell ratings. They suggest many potential conflicts of interest, such as preserved relationships with company management departments, as one of several

factors that deter analysts from issuing sell ratings. This trend suggests that hold ratings may often serve as a softer alternative to their sell counterpart, particularly when analysts wish to indicate their negative sentiment without severing ties with the company for which they are rating.

Niklas Karlsson, George Loewenstein, and Duane Seppi suggest that analysts may reserve a cognitive bias in favor of buy or hold ratings to avoid the discomfort associated with the negative implications of sell ratings. In truth, an issued hold rating may bear more negative connotations than it appears on the surface.

The Financial Times, in an article published in 2012, touched upon this issue by asserting that the rarity of sell ratings may result from analysts’ fear of losing corporate access. The AnaChart data support this view, showing that analysts are more likely to upgrade from a sell to a hold than from a sell to a buy (11,965 instances compared to 1,528).

Ratings Change Timing

Another aspect of stock ratings conspicuously absent from academia is the timing when analysts switch ratings. While examining thousands of interactions between analysts and stocks, we have noticed that when analysts lose faith in the stocks they cover, they tend to switch over to a hold rating in correlation with the decline of that stock price.

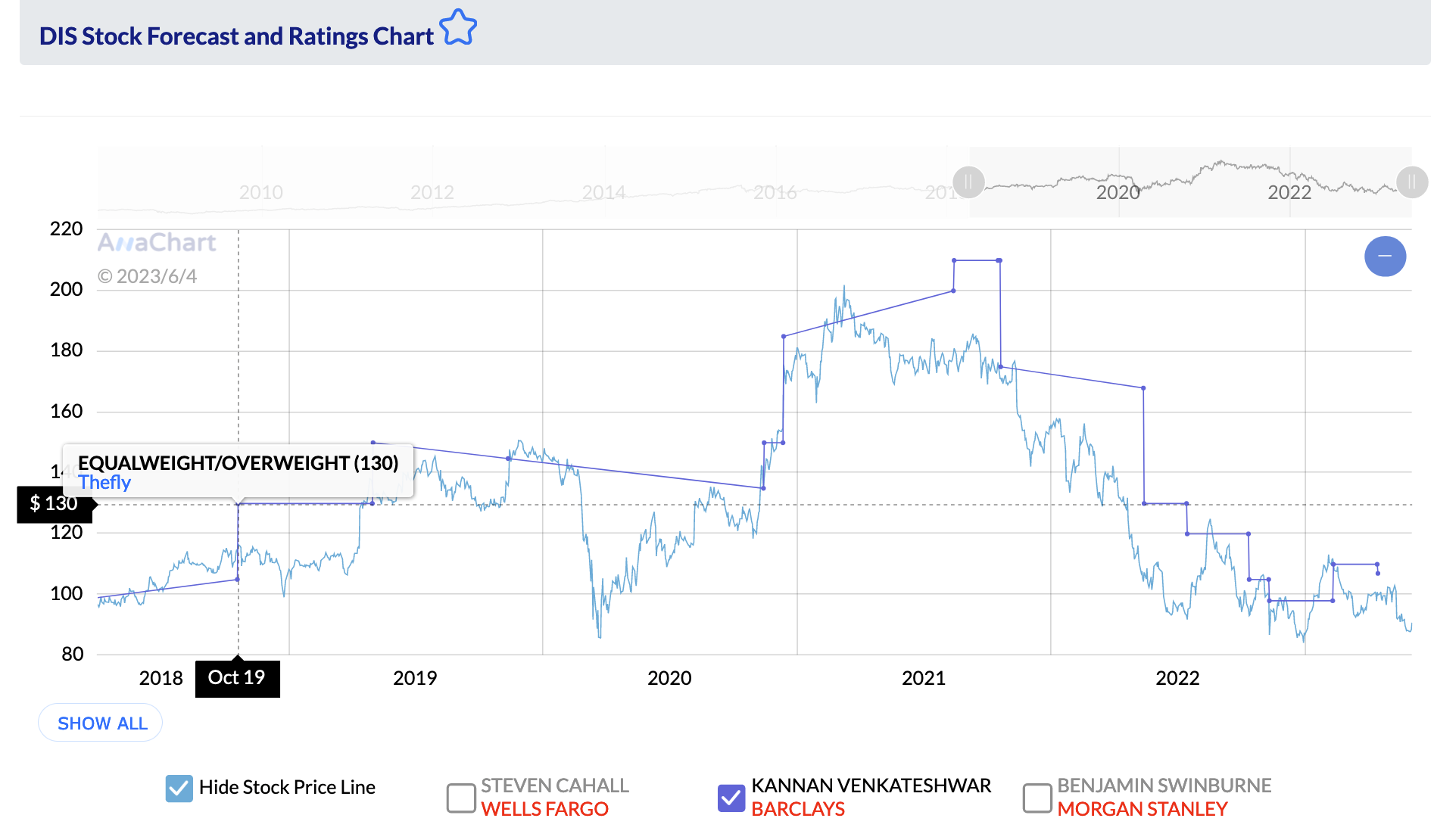

For a better example, look at the rating history of stock analyst Kannan Venkateshwar from Barclays, who has covered Walt Disney stock for over ten years.

When the Analyst Shows Faith (or Lack Of)

Glancing at the first snapshot, we see Venkateshwar switches his rating from equal weight (equivalent to a hold rating) to overweight (equivalent to a buy rating) on October 19, 2018 (while also raising his price target to $130 from $105). As you

can see, he made a call well in advance, which is a sure sign the analyst has confidence in the future financial success of a company.

Two years later, once losing his belief that the Walt Disney stock the Barclays analyst chose to switch to a hold rating rather than a sell (accompanied by lowering his price target to show little potential upside).

Conclusion

Stock sell rating takes place only of a small fraction of the stock rating universe. As such, Investors should consider looking at hold rating as more of “not a buy” rather than a form of neutrality, in particular when taking into account the stock price movement.